Efficiency: Desirable, possible, and doable

One disadvantage in the public service sector is that it is hard to gauge efficiency. Profit per staff member or procurements (projects) won can be determined, but there are too many factors not under the organization’s control that influence this variable. So what does efficiency in the nonprofit sector mean?

Over the last few years I have been involved in an experiment; spearheaded by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the Program for Humanitarian Impact Investment developed a single indicator in order to determine whether social investors will see a return on their investment or not. The ratio is a formula that includes hours of work, per staff category, to make various orthopedic devices and total work hours per week. If people actually work a full workweek and produce many (quality) devices, the value of the indicator goes up. If people don’t, it goes down. By the way, all the variables involved in this calculation are within the sphere of influence of the rehabilitation center itself.

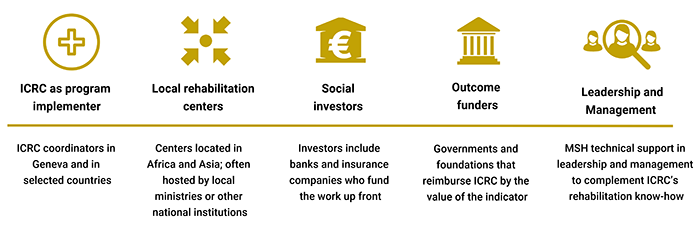

Five parties are involved in this impact investment initiative:

The initiative is designed based on four critical drivers of efficiency:

- a deep understanding of the technical and managerial processes in use;

- periodic collection of critical performance data;

- a well-constructed plan with indicators, responsibilities, and timelines that is monitored and updated on a monthly basis; and

- a series of practical management and leadership tools.

All this sounds like common sense. But program managers have been trained in these areas for decades, with sometimes little to show for it. The challenge, which is a real consideration here, is that it is too early to determine whether this approach will (literally) pay off, especially in those centers that started from a very low bar.

Returning recently from a visit to one of the teams participating in this initiative, the national rehabilitation center in Mali, I have seen the four efficiency drivers in action – progress is slow as it requires center staff to change their work behaviors and habits, but there is movement in the right direction. Progress is progress and it can be measured, using the efficiency drivers listed above. Now that the team is seeing its first small victories, another layer of drivers has come into view: drivers to bring about a cultural change. They are about social norms—behaviors and habits that are deemed acceptable or not in a specific context—that are often difficult to identify, but powerful facilitators or barriers to change. These cultural drivers become critical when the attention and resources associated with the initiative will disappear (in less than two years). Maintaining the efficiencies gained over the long run will be the ultimate test of this initiative.

If improving the four efficiency drivers (processes, data collection, plans, and management tools—which are relatively tangible and defined) is challenging, then the cultural drivers are even more difficult to activate and maintain, as they are about behavior, habits, and norms. Interventions focused on improving effectiveness and efficiency often concentrate so much on producing specific results that the foundation needed to maintain those good results over time is forgotten. Where such a base is missing none of the results in efficiency and effectiveness are likely to withstand the ebb and flow of resources (whether money, people, equipment, supplies).

So how can we create the strong foundation?

It requires putting into focus, and questioning, the behavior of every employee in the organization to make sure it supports the new efficiencies. The big challenge is thus for those who lead the initiative inside the organization. Only the leadership team of the rehabilitation center on the ground can make efficiency stick—not the ICRC coordinators in Geneva, not the local ICRC staff, not the investors, not the outcome funders, and not the MSH consultants. Local rehabilitation managers and their teams will have to set the right tone that will change the culture, the habits, the behaviors and the norms inside the organization and advocate for those outside to support them.

About the Author

After working for Management Sciences for Health (MSH) for over 30 years, Sylvia Vriesendorp is currently an independent consultant. She was one of the principal developers of MSH’s innovative leadership development programs and the author or co-author of several MSH publications related to leadership development. She earned her coaching credentials from the Institute of Professional Excellence in Coaching and is certified by the International Coach Federation. Over the last few years she has studied the neuroscience of coaching and has been certified as a Conversational Intelligence™ coach. Her consulting and coaching clients range from a large established organization, to several USAID projects and a young startup in Zambia. In addition to her consulting and coaching practice she has also taught two online MBA courses on leadership and negotiation at Simmons University.

Thank you Sylvia for sharing this great piece. I totally agree with your assertion “Only the leadership team of the rehabilitation center on the ground can make efficiency stick—not the ICRC coordinators in Geneva, not the local ICRC staff, not the investors, not the outcome funders, and not the MSH consultants”.

This is so critical to achieving the sustainability and more recently, the self reliance objective of many funders. Without committment from leadership, the gains made through funded projects will hardly survive the end of external funding. It bears repeating that such committment need to include committment of financial resources. Leaders need to put their monies where their mouths are. Sustainability and self reliance also need local resources to stick.